The First HSOC Consecration

How to Read the Bible and Why

The Bible is in a sense a biography of God in this world. In it the Indescribable One has in a sense described Himself.

The Holy Scriptures of the New Testament are a biography of the incarnate God in this world. In them it is related how God, in order to reveal Himself to men, sent God the Logos, who took on flesh and became man–and as a man told men everything that God is, everything that God wants from this world and the people in it.

God the Logos revealed God’s plan for the world and God’s love for the world. God the Word spoke to men about God with the help of words, insofar as human words can contain the uncontainable God.

All that is necessary for this world and the people in it–the Lord has stated in the Bible. In it He has given the answers to all questions. There is no question which can torment the human soul, and not find its answer, either directly or indirectly in the Bible.

Men cannot devise more questions than there are answers in the Bible. If you fail to find the answer to any of your questions in the Bible, it means that you have either posed a sense-less question or did not know how to read the Bible and did not finish reading the answer in it.

Men cannot devise more questions than there are answers in the Bible. If you fail to find the answer to any of your questions in the Bible, it means that you have either posed a sense-less question or did not know how to read the Bible and did not finish reading the answer in it.

In the Bible God has made known:

[1] what the world is; where it came from; why it exists; where it is heading; how it will end;

[2] what man is; where he comes from; where he is going; what he is made of; what his purpose is; how he will end;

[3] what animals and plants are; what their purpose is; what they are used for;

[4] what good is; where it comes from; what it leads to; what its purpose is; how it is attained;

[5] what evil is; where it comes from; how it came to exist; why it exists–how it will come to an end;

[6] what the righteous are and what sinners are; how a sinner becomes righteous and how an arrogant flghteous man becomes a sinner; how a man serves God and how he serves satan; the whole path from good to evil, and from God to satan;

[7] everything–from the beginning to the end; man’s entire path from the body to God, from his conception in the womb to his resurrection from the dead;

[8] what the history of the world is, the history of heaven and earth, the history of mankind; what their path, purpose, and end are.

In the Bible God has said absolutely everything that was necessary to be said to men. The biography of every man-everyone without exception–is found in the Bible.

In it each of us can find himself portrayed and thoroughly described in detail: all those virtues and vices which you have and can have and cannot have.

You will find the paths on which your own soul and everyone else’s journey from sin to siniessness, and the entire path from man to God and from man to Satan. You will find the means to free yourself from sin.

In short, you will find the complete history of sin and sinfulness, and the complete history of righteousness and the righteous.

If you are mournful, you will find consolation in the Bible; if you are sad, you will find joy; if you are angry–tranquility; if you are lustful–continence; if you are foolish–wisdom; if you are bad–goodness; if you are a criminal–mercy and righteousness; if you hate your fellow man–love.

In it you will find a remedy for all your vices and weak points, and nourishment for all your virtues and accomplishments.

If you are good, the Bible will teach you how to become better; if you are kind, it will teach you angelic tenderness; if you are intelligent, it will teach you wisdom.

If you appreciate the beauty and music of literary style, there is nothing more beautiful or more moving than what is contained in Job, Isaiah, Solomon, David, John the Theologian and the Apostle Paul. Here music–the angelic music of the eternal truth of God–is clothed in human words.

The more one reads and studies the Bible, the more he finds reasons to study it as often and as frequently as he can. According to St. John Chrysostom, it is like an aromatic root, which produces more and more aroma the more it is rubbed.

Just as important as knowing why we should read the Bible is knowing how we should read the Bible.

The best guides for this are the holy Fathers, headed by St. John Chrysostom who, in a manner of speaking, has written a fifth Gospel.

The holy Fathers recommend serious preparation before reading and studying the Bible; but of what does this preparation consist?

First of all in prayer. Pray to the Lord to illuminate your mind–so that you may understand the words of the Bible–and to fill your heart with His grace–so that you may feel the truth and life of those words.

Be aware that these are God’s words, which He is speaking and saying to you personally. Prayer, together with the other virtues found in the Gospel, is the best preparation a person can have for understanding the Bible.

How should we read the Bible? Prayerfully and reverently, for in each word there is another drop of eternal truth, and all the words together make up the boundless ocean of the Eternal Truth.

The Bible is not a book but life; because its words are “spirit and life” (John 6:63). Therefore its words can be comprehended if we study them with the spirit of its spirit, and with the life of its life.

It is a book that must be read with life–by putting it into practice. One should first live it, and then understand it.

Here the words of the Saviour apply: “Whoever is willing to do it–will understand that this teaching is from God” (John 7:17). Do it, so that you may understand it. This is the fundamental rule of Orthodox exegesis.

At first one usually reads the Bible quickly, and then more and more slowly, until finally he will begin to read not even word by word, because in each word he is discovering an everlasting truth and an ineffable mystery.

Every day read at least one chapter from the Old and the New Testament; but side by side with this put a virtue from each into practice. Practice it until it becomes a habit to you.

Let us say, for instance, that the first virtue is forgiveness of insults. Let this be your daily obligation. And along with it pray to the Lord: “O gentle Lord, grant me love towards those who insult me!”

And when you have made this virtue into a habit, each of the other virtues after it will be easier for you, and so on until the final one.

The main thing is to read the Bible as much as possible. When the mind does not understand, the heart will feel; and if neither the mind understands nor the heart feels, read it over again, because by reading it you are sowing God’s words in your soul.

And there they will not perish, but will gradually and imperceptibly pass into the nature of your soul; and there will happen to you what the Saviour said about the man who “casts seed on the ground, and sleeps and rises night and day, and the seed sprouts and grows, while the man does not know it” (Mark 4:26-27).

The main thing is: sow, and it is God who causes and allows what is sown to grow (1 Cor. 3:6). But do not rush success, lest you become like a man who sows today, but tomorrow already wants to reap.

By reading the Bible you are adding yeast to the dough of your soul and body, which gradually expands and fills the soul until it has thoroughly permeated it and makes it rise with the truth and righteousness of the Gospel.

In every instance, the Saviour’s parable about the sower and the seed can be applied tp every one of us. The seed of Divine Truth is given to us in the Bible.

By reading it, we sow that seed in our own soul. It falls on the rocky and thorny ground of our soul, but a little also falls on the good soil of our heart–and bears fruit.

And when you catch sight of the fruit and taste it, the sweetness and joy will spur you to clear and plow the rocky and thorny areas of your soul and sow it with the seed of the word of God.

Do you know when a man is wise in the sight of Christ the Lord? –When he listens to His word and carries it out. The beginning of wisdom is to listen to God’s word (Matt. 7:24-25).

Every word of the Saviour has the power and the might to heal both physical and spiritual ailments. “Say the word and my servant will be healed” (Matt. 8:8). The Saviour said the word–and the centurion’s servant was healed.

Just as He once did, the Lord even now ceaselessly says His words to you, to me, and to all of us. But we must pause, and immerse ourselves in them and receive them–with the centurion’s faith.

And a miracle will happen to us, and our souls will be healed just as the centurion’s servant was healed. For it is related in the Gospel that they brought many possessed people to Him, and He drove out the spirits with a word, and healed all the sick (Matt. 8:16).

He still does this today, because the Lord Jesus “is the same yesterday and today and forever” (Heb. 13:8)

Those who do not listen to God’s words will be judged at the Dreadful Judgment, and it will be worse for them on the Day of Judgment than it was for Sodom and Gomorrah (Matt. 10:14-15).

Beware–at the Dreadful Judgment you will be asked to give an account for what you have done with the words of God, whether you have listened to them and kept them, whether you have rejoiced in them or been ashamed of them.

If you have been ashamed of them, the Lord will also be ashamed of you when He comes in the glory of His Father together with the holy angels (Mark 8:38).

There are few words of men that are not vain and idle. Thus there are few words for which we do not mind being judged (Matt. 12:36).

In order to avoid this, we must study and learn the words of God from the Bible and make them our own; for God proclaimed them to men so that they might accept them, and by means of them also accept the Truth of God itself. In each word of the Saviour there is more eternity and permanence than in all of heaven and earth with all their history.

Hence He said: “Heaven and earth will pass away, but my words will not pass away” (Matt. 24:35). This means that God and all that is of God is in the Saviour’s words. Therefore they cannot pass away.

If a man accepts them, he is more permanent than heaven and earth, because there is a power in them that immortalizes man and makes him eternal.

Learning and fulfilling the words of God makes a person a relative of the Lord Jesus. He Himself revealed this when He said: “My mother and my brothers are those who hear the word of God and carry it out” (Luke 8:21).

This means that if you hear and read the word of God, you are a half-brother of Christ. If you carry it out, you are a full brother of Christ. And that is a joy and privilege greater than that of the angels.

In learning from the Bible, a certain blessedness floods the soul which resembles nothing on earth. The Saviour spoke about this when He said, “Blessed are those who hear the word of God and keep it” (Luke 11:28).

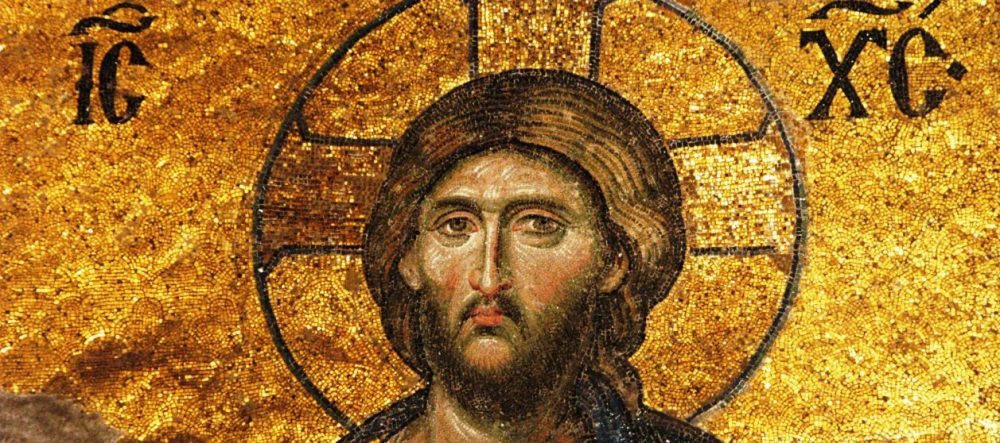

Great is the mystery of the word–so great that the second Person of the Holy Trinity, Christ the Lord, is called “the Word” or “the Logos” in the Bible.

God is the Word (John 1:1). All those words which come from the eternal and absolute Word are full of God, Divine Truth, Eternity, and Righteousness. If you listen to them, you are listening to God. If you read them, you are reading the direct words of God.

God the Word became flesh, became man (John 1:14), and mute, stuttering man began to proclaim the words of the eternal truth and righteousness of God.

In the Saviour’s words there is a certain elixir of immortality, which drips drop by drop into the soul of the man who reads His words and brings his soul from death to life, from impermanence to permanence.

The Saviour indicated this when He said: “Truly, truly I say unto you, whoever listens to my word and believes in the One who sent me has eternal life …and has passed over from death to life” (John 5:24).

Thus the Saviour makes the crucial assertion: “Truly, truly I say unto you, whoever keeps my words will never see death” (John 8:51).

Every word of Christ is full of God. Thus, when it enters a man’s soul it cleanses it from every defilement. From each of His words comes a power that cleanses us from sin.

Hence at the Mystical Supper the Saviour told His disciples, who used to listen to His word without ceasing: “You have already been cleansed by the word which I have spoken to you” (John 15:3).

Christ the Lord and His Apostles call everything that is written in the Bible the word of God, the word of the Lord (John 17:14; Acts 6:2, 13:46, 16:32, 19:20; II Cor. 2:17; Col. 1:15, II Thess. 3:1), and uniess you read it and receive it as such, you will remain in the mute, stuttering words of men, vain and idle.

Every word of God is full of God’s Truth, which sanctifies the soul for all eternity once it enters it.

Thus does the Saviour turn to His heaveniy Father in prayer: “Father! Sanctify them with Thy Truth; Thy word is truth” (John 17:17).

If you do not accept the word of Christ as the word of God, as the word of the Truth, then falsehood and the father of lies within you is rebelling against it.

In every word of the Saviour there is much that is supernatural and full of grace, and this is what sheds grace on the soul of man when the word of Christ visits it.

Therefore the Holy Apostle calls the whole structure of the house of salvation “the word of the grace of God” (Acts 20:32).

Like a living grace-filled power, the word of God has a wonder-working and life-giving effect on a man, so long as he hears it with faith and receives it with faith (1 Thess. 2:13).

Everything is defiled by sin, but everything is cleansed by the word of God and prayer–everything–all creation from man on down to a worm (1 Tim. 4:5).

By the Truth which it carries in itself and by the Power which it has in itself, the word of God is “sharper than any sword and pierces to the point of dividing soul and spirit, joints and marrow, and discerns the thoughts and intentions of the heart” (Heb. 4:12). Nothing remains secret before it or for it.

Because every word of God contains the eternal Word of God–the Logos-it has the power to give birth and regenerate men. And when a man is born of the Word, he is born of the Truth.

For this reason St. James the Apostle writes to the Christians that God the Father has brought them forth “by the word of truth” (1:18); and St. Peter tells them that they “have been born anew…by the word of the living God, which abides forever” (1 Peter 1:23).

All the words of God, which God has spoken to men, come from the Eternal Word–the Logos, who is the Word of life and bestows Life eternal.

By living for the Word, a man brings himself from death to life. By filling himself with eternal life, a man becomes a conqueror of death and “a partaker of the Divine nature” (2 Peter 1:4), and of his blessedness there shall be no end.

The main and most important point of all this is faith and feeling love towards Christ the Lord, because the mystery of every word of God is opened beneath the warmth of that feeling, just as the petals of a fragrant flower are opened beneath the warmth of the sun’s rays. Amen.